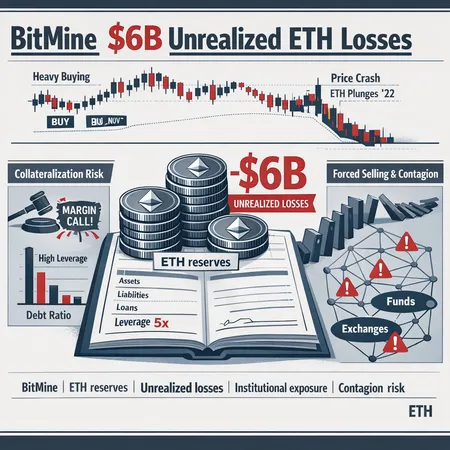

BitMine’s $6B ETH Paper Loss: What Institutional ETH Reserves Mean for Market Stability

Summary

Executive summary

BitMine — reported to have built a very large Ether position — is now sitting on roughly $6 billion in unrealized losses, according to multiple news reports. That number is not a definitive statement of insolvency, but it is a red flag for market-structure watchers: large concentrated ETH balances held by an institutional player change how liquidity, collateral and counterparty risk behave in a downturn. This explainer walks through how those reserves were likely accumulated, the mechanics of unrealized losses, the balance-sheet and collateral risks they create, plausible forced‑selling pathways, and what analysts should watch next.

How BitMine accumulated large ETH reserves (and why the timing matters)

Public reporting indicates BitMine amassed a material position in ETH over an extended period before the recent price slide (CoinDesk). Institutions typically build such reserves via OTC desks, exchange purchases and programmatic buys. The incentives are clear: staking yield, narrative-driven appreciation, and portfolio diversification away from cash equivalents.

Timing matters because many large buys reportedly occurred ahead of the down move. When an institution front-loads accumulation at higher prices, it increases the distance between book cost and eventual market value if the market reverses. News outlets tracking the story — including CryptoNews and follow-up pieces showing the firm doubling down despite the hit (CoinTribune) — suggest a concentrated buy strategy rather than a slow, dollar-cost-averaged accumulation.

For market participants, that difference is vital: staggered accumulation spreads mark‑to‑market risk over time; lump-sum or concentrated buys leave a single balance-sheet line vulnerable to sharp re-rating.

Unrealized losses: accounting mechanics and why they matter beyond 'paper'

An unrealized loss is simply the gap between the current market price and the acquisition cost of an asset that hasn't been sold. On its own, it’s a paper loss. But for institutions that use assets as collateral or that report mark-to-market valuations to counterparties and regulators, unrealized losses have practical consequences.

- Mark-to-market accounting reduces reported equity when asset prices fall, tightening capital ratios used by lenders and counterparties.

- Collateral haircuts rise as volatility and price risk increase; the same ETH can secure less borrowing capacity.

- Credit lines and repo facilities often include covenants tied to collateral value, so falling valuations can trigger margin calls or reductions in available leverage.

So although BitMine’s $6B figure is an unrealized number, it can quickly become operationally binding: reduced collateral value, higher financing costs, and tighter liquidity — each of which can force an institution to realize losses by selling.

Balance-sheet and collateralization risks specific to large ETH holdings

Large ETH reserves introduce several interlinked balance-sheet vulnerabilities:

- Concentration risk: holding a significant portion of liquid supply in one balance sheet magnifies market impact when selling.

- Collateralization mismatch: institutions that buy ETH for appreciation but also use ETH as collateral for dollar funding can face haircuts that shrink borrowing capacity right when funding needs rise.

- Funding liquidity risk: even profitable firms can struggle if short-term funding evaporates — a classic systemic pathway where solvent firms become illiquid.

If BitMine or a similar actor pledged ETH into lending markets, custody arrangements, or swap collateral, counterparties may demand additional collateral when prices fall. The interplay between asset-liability maturity (short-term borrowings vs. long-duration holdings) determines how fast de-risking must occur.

Plausible forced‑selling scenarios and transmission channels

There are several realistic ways unrealized losses translate into actual market stress:

Margin calls and exchange‑leveraged positions — If ETH is posted on margin at centralized counterparties, the typical response to price drops is a margin call or liquidation. Selling pressure from automated liquidations is fast and concentrated.

Repo and bilateral lending squeezes — Collateral haircuts increase, counterparties reduce lines, and the borrower must either post more collateral or sell assets to meet obligations.

Staking and withdrawal lags — If reserves are locked in staking or validator setups, there can be operational friction in extracting liquidity quickly, leading firms to sell non-staked holdings at a worse price.

Off‑balance-sheet counterparties — Credit support annexes, rehypothecation and derivatives netting can create opaque chains of exposures; a forced sale at one node spills over to others.

In each pathway the immediate effect is the same: concentrated selling into an already stressed market reduces depth, increases spreads, and amplifies price moves. That’s how an individual firm’s balance-sheet problem becomes a market event.

Contagion risk: why one institution’s trouble can become a system problem

Contagion doesn’t require insolvency at the origin. Two features of crypto markets make contagion more likely than in many traditional markets:

- Higher leverage and rehypothecation: crypto lending and desk ecosystems routinely reuse collateral, increasing interconnectedness.

- Variable liquidity across venues: decentralized pools can look deep on paper but become shallow during concentrated selling due to slippage and price impact.

A large, fast sell order can push ETH prices lower, re‑marking similar positions across custodians and funds and triggering further de-risking. That snowball — margin calls, liquidations, spikes in funding rates — can spread from centralized platforms to DeFi protocols, and vice versa, creating cross‑venue contagion. History shows that when liquidity providers pull back, options skews widen and volatility begets volatility.

Broader implications for institutional ETH accumulation strategies

The BitMine episode forces a re-evaluation of how institutions approach large stakes in ETH:

- Pace and disclosure: slow, staggered accumulation reduces mark-to-market concentration. Transparent reporting (where appropriate) can reduce counterparty uncertainty.

- Collateral planning: if ETH is used to fund operations, firms must build buffers for haircuts and ensure diversified collateral mixes.

- Liquidity buffers: hold a mix of liquid cash or stablecoins that can be used to meet short-term liabilities without selling core holdings.

Institutional appetite for ETH will continue because of staking yield and protocol-level growth, but prudent treasury management — stress testing, limits on rehypothecation, and contingency liquidity plans — becomes essential when positions reach market‑swaying scale.

What analysts, allocators and journalists should watch now

Analytical signals and public metrics can give early warning of stress:

- Exchange reserve flows: sudden outflows or inflows to major exchanges can signal upcoming selling pressure.

- Open interest and funding rates in ETH futures/options: rising open interest with widening basis or extreme funding suggests leveraged positions are at risk.

- On‑chain concentration: large transfers between cold wallets, staking contracts and custodians often precede position rebalancing.

- Counterparty disclosures and margin notifications: while harder to obtain, regulatory filings and public statements can reveal funding stress.

Combine on‑chain monitoring with traditional credit‑risk flags (counterparty concentration, repo counterparties, collateral rehypothecation). Third-party vendors and services — including institutional settlement and lending desks, and solutions such as Bitlet.app for invoicing and settlement — are useful elements in the operational toolkit but do not substitute for rigorous stress tests.

Scenario testing: quick, medium and extreme outcomes

- Quick de‑risk: BitMine secures additional funding lines or posts alternate collateral; sells a limited tranche of ETH into deep liquidity; markets absorb the flow with muted contagion.

- Medium stress: collateral haircuts escalate, forcing more sales; volatility spikes; some leveraged counterparties liquidate but broader solvency is preserved via recapitalizations or fire sales to strategic buyers.

- Extreme cascade: forced selling hits thin order books, derivatives margins spike, and multiple institutions face liquidity crises — a classic contagion loop that can push ETH lower and impair funding markets broadly.

Probability and impact depend on balance‑sheet flexibility, inter‑counterparty exposures, and overall market liquidity at the time of any forced moves.

Conclusion — not just a BitMine story, but a market‑structure moment

BitMine’s reported $6 billion unrealized loss is a useful case study in the risks that come with concentrated institutional ETH exposure. Unrealized losses are signals, not verdicts — but they can trigger operational events (margin calls, haircuts, liquidity squeezes) that convert paper losses into realized market stress. For institutional investors and analysts, the lesson is straightforward: large crypto balance sheets require the same bail‑out‑proofing and stress testing that big traditional financial institutions face. Monitor the right metrics, demand transparency in counterparty collateral practices, and plan for liquidity contingencies.

Sources