Quantum Risk to Bitcoin and Zero‑Knowledge: A Technical Mitigation Roadmap

Summary

Executive overview

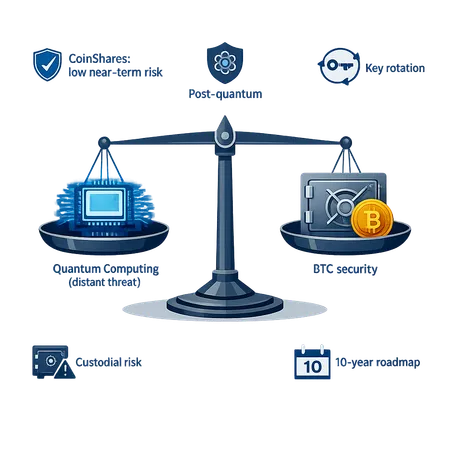

Quantum computing poses a real but uncertain threat to current Bitcoin security because BTC’s signatures and key management are built on elliptic‑curve assumptions that Shor‑style algorithms would defeat. The technical community is split on urgency and tactics: some argue for cautious monitoring and conservative engineering, while others push for active mitigation now. This article explains the cryptographic exposure, surveys industry timeline views, outlines how zero‑knowledge can provide a pragmatic, non‑consensus migration path, and gives a prioritized checklist custodians and protocol teams can act on today.

For many teams the primary question is tactical: how do you reduce custody risk without risking a disruptive consensus hard fork? Zero‑knowledge methods and off‑chain wrapping approaches present realistic options for that middle ground.

What part of Bitcoin is vulnerable to quantum attacks?

At a high level the risk comes from two quantum primitives:

- Shor’s algorithm — gives an efficient method to solve discrete logarithms and integer factorization on a sufficiently large, error‑corrected quantum computer. That directly targets elliptic‑curve private keys.

- Grover’s algorithm — provides a quadratic speedup for symmetric key search, meaning symmetric-security parameters need to be doubled to maintain equivalent security.

Bitcoin’s on‑chain authentication relies on elliptic‑curve signatures (ECDSA historically, now Taproot uses Schnorr-like constructs). If an attacker can compute the discrete log of a public key, they can derive the private key and produce valid signatures to spend funds.

Practical attack surface points:

- Public key exposure: Bitcoin addresses created from a hash of a public key (e.g., P2PKH) do not expose the raw public key until the UTXO is spent. Once a UTXO is spent, the public key appears on‑chain and becomes a target. Any reused address or already‑revealed pubkey is therefore at higher risk.

- Signatures and ephemeral data: classical signature leaks (bad nonce reuse) remain issues today; quantum changes the game because even correct signatures become breakable once a strong quantum computer exists.

- Long‑tail custody: funds held for decades (cold storage, endowments) are the highest‑value targets for a future quantum adversary with time to prepare and compute.

The immediate implication: avoid revealing public keys unnecessarily, minimize address reuse, and treat long‑term holdings as high priority for migration planning.

Timeline estimates and the industry debate

There is wide disagreement about when a quantum adversary will realistically threaten BTC. That divergence shapes policy.

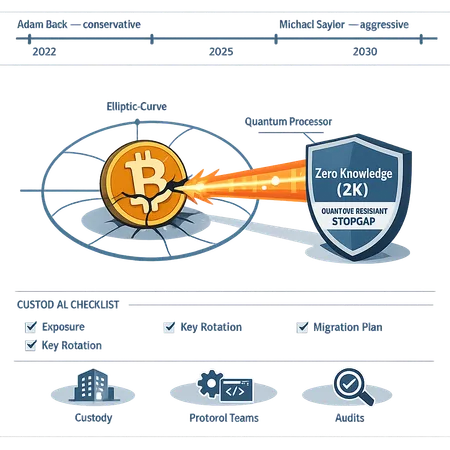

Michael Saylor and others have emphasized a near‑term risk narrative and pushed for accelerated migration planning. Saylor has framed quantum as a durable risk vector that merits aggressive action and public awareness (Bitcoinist article on Saylor’s thesis).

Conversely, engineering conservatives — prominently Adam Back at Blockstream — warn against alarmism and premature protocol changes, arguing the practical quantum threat is not immediate and many risk scenarios are overstated (Blockstream CEO pushes back). Back’s view favors measured monitoring, R&D, and targeted mitigation rather than sweeping, urgent hard forks.

Independent technical commentary highlights nuance: quantum hardware progress is accelerating, but building a fault‑tolerant machine capable of running Shor at the scale to break secp256k1 remains a major engineering lift. Forecasts vary from a decade to several decades; uncertainty is large.

Given this uncertainty, most practitioners are moving toward risk‑tiered responses rather than a single universal strategy.

Why zero‑knowledge is attractive as a pragmatic mitigation layer

Zero‑knowledge constructions are compelling because they enable proofs of control or authorization without revealing sensitive verification material (like a long‑lived public key). There are three complementary reasons ZK is being proposed as a practical stopgap that avoids immediate consensus forks:

Reduce on‑chain exposure without changing Bitcoin’s signature rules. Custodians can construct guardrails or wrapping contracts on layer‑2 or sidechain rails that accept ZK proofs proving ownership or the right to move funds, without broadcasting the raw public key on the main BTC UTXO set.

Enable controlled migration and escrow patterns. Funds can be moved into constructs that require a ZK proof to release them. If those ZK primitives are built atop post‑quantum assumptions (e.g., lattice‑based commitments or hash‑based constructions), the wrapping layer can provide quantum resistance as an operational shield while the community plans longer‑term protocol transitions.

Avoid emergency hard forks. Because many ZK mitigations can be implemented off‑chain, custodians and service providers can adopt them unilaterally without requiring an immediate change to Bitcoin consensus rules — a major practical advantage.

The idea of using ZK as a quantum‑resistant layer has been explored in the literature; for one explanation of how ZK might act as a protective layer for Bitcoin and other chains, see a technical overview at Crypto‑Economy that frames ZK cryptography as a potential quantum‑resistant toolset (crypto‑economy article).

Important caveat: many deployed ZK systems today use primitives (elliptic‑curve pairings, SNARK elliptic curves) that are not quantum‑safe. A real quantum‑resistant ZK layer must be designed on post‑quantum assumptions (e.g., lattice schemes, hash‑based schemes) and audited accordingly.

Concrete ZK patterns that avoid a consensus hard fork

Below are practical ZK‑centered patterns that custodians and protocol teams can evaluate. Each pattern aims to reduce on‑chain public‑key exposure or provide a migration path without changing Bitcoin consensus.

ZK‑wrapped custody (layer‑2 vault): Custody provider moves BTC into a multi‑sig or P2SH wrapper and issues a ZK proof off‑chain that the custodian controls the underlying keys and has authorized a spend. The ZK layer releases funds on a second‑layer contract when proof conditions are met.

Shielded migration windows: Use timelocks combined with ZK proofs: deposit funds into a vault that can be recovered via a ZK proof before a deadline. If a quantum threat materializes, custodians can prove control and move funds without revealing keys publicly.

Blind signature / commitment schemes for key rotation: Rather than publishing permanent pubkeys, custody solutions can commit to key material in a way that later allows ZK proofs of knowledge of the committed secret, enabling key rotation without revealing prior keys.

Each option requires engineering work, operational controls, and cryptanalysis of the chosen post‑quantum primitives.

Engineering conservatism vs aggressive mitigation: practical implications

The community debate is not merely academic. Positions translate into policies:

Conservative approach (Adam Back et al.): Monitor progress, invest in R&D, harden best practices (no key reuse, fast migration paths), and avoid panic‑driven protocol changes. The conservative approach values stability: unnecessary urgent changes introduce risk, complexity, and can break wallet interoperability.

Aggressive approach (Saylor/others): Actively deploy mitigations, accelerate migration of long‑tail holdings, and demand faster adoption of quantum‑resistant constructs. This camp argues that the cost of inaction could be catastrophic for high‑value custodial holdings.

Both camps converge on a pragmatic middle path: treat the risk seriously for high‑value, long‑duration holdings and build migration playbooks now, while continuing measured protocol‑level research and gradual deployment of vetted post‑quantum schemes.

Checklist — prioritized actions for custodians and protocol teams

This checklist is organized by timeframe and priority. It’s intended for CTOs, custody engineers, and protocol teams evaluating quantum resistance and custody risk.

Immediate (days–weeks)

- Inventory keys and exposures: list UTXOs, address types, date created, and whether public keys are revealed on‑chain. Prioritize long‑held, high‑value UTXOs.

- Stop address reuse across products; enforce unique address per deposit with strong wallet hygiene.

- Harden operational controls: multi‑person approvals, air‑gapped key generation, and strict nonce practices for signatures.

- Establish quantum monitoring: subscribe to hardware road‑maps, academic publications, and build a simple threat‑trigger dashboard.

Near term (1–12 months)

- Migrate or segregate at‑risk funds: move long‑duration holdings into accounts with explicit migration plans and shorter exposure windows.

- Evaluate ZK wrapping pilots: prototype a ZK‑wrapped vault or layer‑2 custody trial that proves control without revealing pubkeys. Ensure the ZK primitives chosen are post‑quantum or designed to be replaceable.

- Assess multi‑sig and threshold upgrades: adopt key‑sharing schemes that make full key compromise more difficult and can be rotated without full chain changes.

- Update SLAs and legal frameworks to include quantum‑risk clauses and migration commitments for institutional clients.

Medium term (1–3 years)

- Run migration drills: periodically exercise moving funds from legacy keys to new post‑quantum or ZK‑protected constructs under time pressure.

- Integrate post‑quantum key options into wallet stacks: prototype lattice‑based or hash‑based signing in parallel and benchmark performance and UX.

- Adopt continuous cryptanalysis program: fund external audits focused on post‑quantum proofs, signature schemes, and ZK constructions.

Long term (3+ years)

- Plan for coordinated protocol upgrades only if necessary: any move to change Bitcoin’s consensus signature scheme must be driven by community consensus and careful roll‑out, but be prepared technically to support migration paths.

- Participate in standards: contribute to post‑quantum and ZK standards for blockchain use‑cases to avoid fragmentation.

Operational notes and priorities

- Prioritize cold‑stored institutional funds and long‑tail endowments — the value at stake and exposure window make them the top mitigation candidates.

- Use time‑based triggers: if monitored quantum indicators cross pre‑agreed thresholds, activate migration playbooks and customer notifications.

- Keep user and regulatory communication clear. For institutional clients, describe risk, mitigation plans, and expected timelines.

Technical appendix: what ZK does — and doesn’t — buy you

What zero‑knowledge can do for quantum risk:

- Hide verification material: ZK can prove knowledge of a secret without publishing the corresponding public key.

- Support alternative trust models: combine ZK with threshold signing to make key extraction harder as an operational matter.

- Enable off‑chain migration: wrap funds in constructs that can be redeemed only with a valid ZK proof.

What ZK alone does not solve:

- If a ZK system itself relies on quantum‑vulnerable primitives (pairings, non‑post‑quantum curves), it does not provide true quantum resistance. Careful primitive selection is mandatory.

- It does not replace the need to eventually migrate consensus‑level primitives if a full‑node protocol change becomes unavoidable in the far future.

For teams exploring ZK mitigations, ensure your chosen ZK stack explicitly documents its post‑quantum threat model and that independent cryptanalysis is part of any deployment plan.

Decision framework for CTOs and lead engineers

When deciding how aggressively to act, answer the following in order:

- What is your exposure window? (How long will these private keys remain unchanged?)

- What is the dollar value and sensitivity of the holdings? (Prioritize high‑value, long‑duration positions.)

- Can you implement a non‑consensus mitigation (ZK wrapping, timelocked vaults) quickly and safely? If yes, prototype it.

- Do you have migration playbooks and drills? If not, build them now.

- Are you tracking quantum hardware and algorithmic milestones with a red/amber/green trigger system? If not, implement it.

Answering those questions gives a defensible posture between panic and paralysis.

Closing thoughts

Quantum computing is a credible technical threat to current elliptic‑curve assumptions underpinning Bitcoin security, but the timeline remains uncertain. Engineering conservatism emphasizes stability and measured R&D; aggressive mitigation emphasizes risk transfer and early action. Zero‑knowledge cryptography offers a practical, intermediate path for many custodians and protocol teams: it can reduce on‑chain exposure, enable migration patterns, and be deployed without an immediate consensus hard fork — provided the ZK stack itself is built on quantum‑resistant primitives and properly audited.

Institutional teams should act now to inventory exposure, implement operational best practices, and pilot ZK‑based or other post‑quantum wrapping models for their highest‑risk assets. Tools and platforms (including custody workflows provided by services such as Bitlet.app) can help operationalize these checks and migrations, but the technical decisions — primitives, audits, migration triggers — must be driven by each institution’s risk profile and accountability framework.

Sources

- "Zero Knowledge Technology — Bitcoin’s Secret Weapon Against the Quantum Threat" — Crypto‑Economy: https://crypto-economy.com/zero-knowledge-technology-bitcoins-secret-weapon-against-the-quantum-threat/

- "Blockstream CEO Adam Back slams Nic Carter over Bitcoin quantum threat claims" — CryptoNews: https://cryptonews.com/news/blockstream-ceo-adam-back-slams-nic-carter-over-bitcoin-quantum-threat-claims/

- "Quantum computing & Bitcoin supply — Michael Saylor" — Bitcoinist: https://bitcoinist.com/quantum-computing-bitcoin-supply-michael-saylor/

For practical Bitcoin engineering discussions see commentary on the long‑term cryptographic roadmaps for Bitcoin and related protocol design work.