Why Bitcoin Miners Like Cleanspark Are Pivoting Toward AI Data Centers

Summary

Executive overview

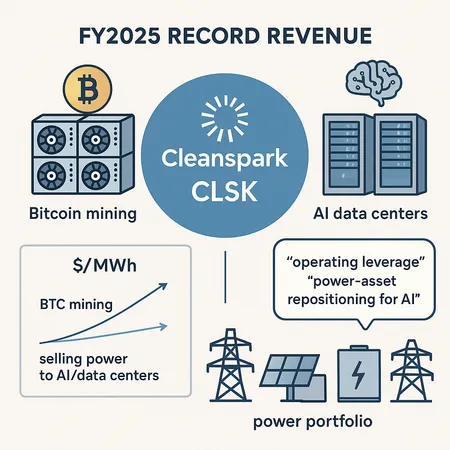

Cleanspark’s recent FY2025 results and accompanying commentary mark a turning point for parts of the mining sector. The company reported record revenue for the year and management explicitly discussed repositioning power assets toward AI and data‑center use cases as part of a broader industrial strategy. This is not merely a footnote — it’s a structural re‑imagining of the miner business model where electricity is a multi‑purpose asset, not only diesel for the hashing engines that generate BTC.

For infrastructure investors and mining executives, the implications are practical and strategic: selling energy to AI customers can deliver steadier USD cashflow and more predictable operating leverage than pure Bitcoin mining, but it also demands different counterparties, contractual disciplines, and capex profiles. Below I unpack Cleanspark’s pivot, compare the economics of selling power to AI/data centers versus mining revenue, and outline what this means for balance sheets and BTC supply dynamics.

Cleanspark’s FY2025 signal: record revenue and an explicit pivot

Cleanspark (CLSK) closed FY2025 with record revenue, and management used the results to highlight two linked themes: operating leverage from scale in both mining and power assets, and an active repositioning of portions of their portfolio to serve AI and data‑center workloads. The company framed these moves as a way to capture higher‑value electrical loads while preserving optionality in its mining operations.

This is emblematic of a broader trend: miners are increasingly viewing on‑site or contracted generation and grid connections as platforms that can host multiple compute customers. The move is less exotic when you consider that the underlying asset — reliable, low‑cost power plus real estate and cooling — is fundamentally the same whether it fuels hashboards or racks of GPUs for model training and inference. Cleanspark’s commentary about operating leverage stresses that once power infrastructure is in place, marginal revenue from higher‑density customers improves fixed‑cost absorption.

For context on how crypto infrastructure and AI are converging, several decentralized AI projects and platforms are emerging to tap blockchain‑native economics and compute markets — a reminder that crossover demand can come from both traditional hyperscalers and crypto‑native AI initiatives. See, for example, profiles of decentralized AI infrastructure efforts that illustrate the demand side for alternative compute models.

Economics: mining revenue vs. selling power to AI/data centers

At a high level, there are four levers that determine whether a miner should keep power for BTC hashing or sell it to AI/data‑center customers:

- Realized revenue per MWh (USD/MWh or $/kWh)

- Revenue volatility and counterparty risk (spot BTC vs contracted USD)

- Utilization and technical fit (continuous hashing vs variable AI workloads)

- Required incremental capex and operating complexity

Qualitatively, AI/data‑center customers often pay a premium for low‑latency, high‑availability power and physical infrastructure. That premium can translate into higher USD/MWh than the realized return from dedicating the same energy to Bitcoin mining — especially in periods when BTC prices are depressed and miner breakevens are squeezed. Conversely, when BTC rallies, mining can dramatically out‑earn contracted power sales.

To make the comparison practical, consider an illustrative example (not Cleanspark‑specific):

- If a miner's marginal cost of electricity is $20/MWh (or $0.02/kWh) and the miner can mine BTC at a realized BTC price that yields the equivalent of $40–$80/MWh in revenue after mining margins, mining could be more attractive in a bull market.

- If an AI or enterprise data‑center will pay $60–$120/MWh under a multi‑year contract for colocated racks and guaranteed uptime, selling to the AI customer becomes attractive for the certainty and USD stability it provides.

Two practical distinctions matter:

- Time horizon and volatility: AI power contracts are usually USD‑denominated, multi‑year, and can be structured with minimum take or pay provisions. Mining revenue is BTC‑denominated and highly volatile, which often forces miners to sell BTC to cover short‑term operating costs.

- Utilization and technical requirements: AI workloads typically need higher rack density, different cooling, and more sophisticated networking. Converting mining halls can require retrofits and changes to operational staffing.

Cleanspark’s message is that by repositioning some power toward AI/data‑center customers, they can lock in higher perimeter margins on those MWs and reduce the company’s sensitivity to BTC price swings while keeping optionality on hashing assets elsewhere in the portfolio.

Balance‑sheet and capital allocation effects

The pivot changes both the income statement cadence and the balance sheet profile for miners. Key effects include:

- Revenue mix and cashflow predictability: More USD‑contracted revenue improves forecasting, lowers the pressure to liquidate BTC, and can smooth quarterly volatility.

- Capex allocation: AI/data center deployments often require different CAPEX (server racks, networking, higher‑tier cooling). However, much of the heavy lifting — grid connection, substations, and land — is already in a miner’s balance sheet, improving the ROI on repurposed sites.

- Financing and credit profile: Predictable, contracted cashflows can enable more favorable financing terms compared to speculative, commodity‑like BTC revenue. Lenders understand term contracts and recurring revenue.

- Depreciation and asset life: GPUs and AI racks have different useful lives than ASICs; mining operators will need to manage mixed depreciation schedules and potential stranded hardware risk if demand shifts.

For investors, the central questions are: can the operator capture sufficient margin per MW to justify conversion costs and complexity, and does the combined portfolio still deliver attractive returns on invested capital compared to pure bitcoin‑focused expansion?

BTC supply dynamics and miner selling behavior

One often overlooked macro effect of this pivot is on BTC supply dynamics. Historically, miners monetize newly minted BTC to cover operational and capital expenses. If a miner substitutes part of that cashflow with USD contracts from AI/data centers, they may have less need to sell bitcoin immediately.

The practical chain of effects:

- Less forced selling: USD revenue from power sales reduces the need to liquidate mined BTC to meet payroll, interest, or maintenance capex.

- Optionality to hold: With lower short‑term liquidity pressure, miners can choose to accumulate BTC on the balance sheet or sell selectively, which can transiently reduce market sell pressure from the miner cohort.

- Net impact on circulating supply: The collective action of large miners gradually shifting revenue sources could reduce the flow of miner‑sold BTC into exchanges, tightening short‑term sell liquidity and potentially amplifying price moves when combined with other demand factors.

That said, miners may also redeploy cash to buy more land, build additional power projects, or buy capacity — decisions that could ultimately increase production and offset any temporary reduction in selling. The net effect on BTC supply and price is therefore nuanced and time‑dependent.

Operational and strategic risks

Repositioning to support AI/data centers is not risk‑free. Consider:

- Execution risk: Retrofitting facilities, negotiating long‑term contracts with AI customers, and meeting SLAs require different capabilities than running a large ASIC fleet.

- Market risk: The AI compute market is crowded and dominated by hyperscalers with deep balance sheets. Miners must find niches (e.g., low‑cost power, geographic advantages, or regulatory arbitrage).

- Regulatory and permitting: Large power projects and data centers face land use, environmental review, and interconnection delays.

- Technology risk: Rapid changes in AI hardware (from GPUs to custom accelerators) could leave colocated infrastructure misaligned with customer needs.

These risks argue for gradual, test‑and‑learn deployments rather than wholesale conversion of mining capacity.

What infrastructure investors and miners should watch

If you’re evaluating this pivot as an investor or executive, focus your diligence on a few measurable items:

- Effective USD/MWh realized from AI/data‑center contracts vs historical realized USD/MWh equivalents from mining across a business cycle.

- Contract length, take‑or‑pay structure, and counterparty credit quality.

- Conversion CAPEX per MW, expected payback period, and incremental OPEX.

- Utilization guarantees and SLAs: can the site meet uptime and latency needs for AI customers?

- Asset optionality and exit pathways if demand for AI racks softens.

Tracking those metrics will separate tactical experiments from durable, scalable strategies.

Conclusion: a hybrid future for the miner business model

Cleanspark’s FY2025 results and strategic commentary crystallize a larger movement: miners increasingly view their power portfolios as multi‑purpose infrastructures that can serve both BTC mining and higher‑margin computing workloads like AI. This repositioning can improve cashflow stability and credit profiles, reduce forced BTC selling, and unlock new valuation frameworks for mining companies.

But it’s not a simple arbitrage. Converting power to AI/data‑center use cases requires operational upgrades, different sales cycles, and exposure to a distinct set of competitors and technology risks. For investors and executives, the smart path is disciplined experimentation, clear metrics, and maintaining optionality so that assets can pivot back to mining if BTC economics become favorable again.

Platforms that track miner flows and BTC custody can help market participants monitor these shifts in near real‑time — for example, Bitlet.app aggregates behavioral signals across mining and exchange flows that investors may find useful.